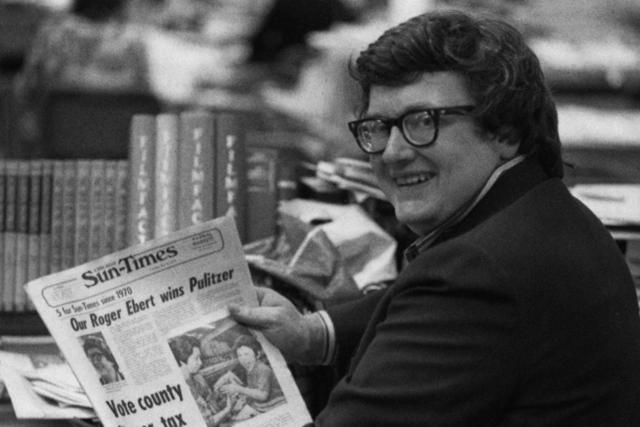

Perhaps, like me, you first came across Roger Ebert's contributions to film criticism as a young kid each time you set foot in a multiplex, where you invariably found yourself staring at a poster-plastered wall decorated with big, emboldened quotes of the “Two thumbs up!” variety. But as anyone who's passionate about film will tell you, there was so much more to the late, Pulitzer Prize-winning “soldier of cinema” than what such an overused platitude might suggest. In his remarkably poignant documentary portrait, Life Itself, acclaimed filmmaker Steve James (Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters) looks back on the life of America's quintessential mainstream film critic: his early years as a general assignment reporter, his alcoholism, his proclivity for large-breasted women, his epic professional rivalry with fellow critic Gene Siskel, marrying Chaz, the love of his life, at 50, and working with a voice synthesizer later on in life. Through it all, cinematic pillars (we're talking Martin Scorsese, Errol Morris and Werner Herzog) weigh in on Ebert's legacy, his refusal to condescend in his reviews and his utter optimism about the future of cinema. Life Itself's unique insights into the history of cinema make it required viewing for any film buff worth his salt. Nightlife.ca spoke with James on the line from Chicago about Ebert's political consciousness, his courageous battle with thyroid cancer and his very Midwestern sensibility.

As a Chicagoan yourself, what do you think kept Ebert from leaving the city to entertain opportunities in New York and Los Angeles?

I think he fell in love with the city and the city fell in love with him. It's a quintessential American city because of where it's located. It has much of the sophistication of New York in certain quarters, but it also has that Midwest thing that New York and L.A. don't have. With Roger being a Midwesterner, I think that was part of what kept him here. It's a brawny, tough kind of city, and all those things appeal to him. I'm just speculating here, but I think at some point, he took pride in being able to do everything he ever wanted to do here, and he wouldn't have to go to New York or L.A., especially as it related to film. With his Pulitzer and his show with Siskel, he put Chicago on the map as a film place.  Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert

In hindsight, what do you make of Richard Corliss' scathing 1990 Film Comment critique of the “Two Thumbs Up” seal of approval popularized by Siskel and Ebert? Did it ultimately prove more beneficial or damaging to the broader film culture?

I'm glad you ask that, I wanted to address it in the film and hear from Corliss and also Roger's rebuttal. While Corliss expressed legitimate concerns, I feel like any survey of filmmakers and particularly younger film critics would find that the program actually did way more good for film than whatever the negative of “thumbs up, thumbs down.” That's because there was actual debate, insight and an exchange of ideas on the show leading up to their decision about whether you should go see a movie or not. I think that encouraged people – particularly everyday viewers – to think more about movies than whether they just liked it or not. That was the end of the show, not the show.

The other thing is that since Life Itself has come out, if you read through all the articles and reviews that have been written about it, you find that an incredible number of people first came to film and film criticism through that show, and have gone on to careers in film. To me, that says volumes about the true underlying value of this show. As Roger says, it's not deep film criticism because they couldn't do that on a TV show. He knew exactly what its limits were, but I think the critiques some people had about the show were too narrow. Your film touches upon many instances in Ebert's career where he took a strong stance on heated political and social issues, whether it be railing against the almighty U.S. gun lobby or the deadly bombing of a Baptist Church by the Ku Klux Klan in 1963. Would it be fair to say Ebert aimed to broaden people's horizons through his writing?

Your film touches upon many instances in Ebert's career where he took a strong stance on heated political and social issues, whether it be railing against the almighty U.S. gun lobby or the deadly bombing of a Baptist Church by the Ku Klux Klan in 1963. Would it be fair to say Ebert aimed to broaden people's horizons through his writing?

Absolutely. I think Roger always cared about what was going on in the world, and passionately so. He was one of those guys that when the paper arrived in the morning, he devoured it. He devoured books – he loved novels, but he also loved non-fiction. He envisioned himself eventually becoming an op-ed columnist after being a beat reporter. That impulse was always strongly there, and you could see that he had a great talent for it from a young age. It's one of the things he brought to his film criticism. Besides film, he wrote about public affairs and social issues that were going on in the world. But even in his film criticism, he especially brought that to bear in his writing about documentaries. He saw films as a way to take us out into the world, not just inside a movie theatre or this fantasy of whatever's on the screen. I think that was part of what made him distinctive as a film critic.

There's that great quote of his that you open the film with, which captures his unique sensibilities so perfectly: that movies are like a machine that generates empathy.

That to me is the most eloquent statement about what film is or what it aspires to be that I've ever heard. I think it especially resonates for those of us who are documentary filmmakers because it goes to the heart of what so many of us try to do.

Your film offers an unflinching look at the toll Ebert's thyroid cancer took on his physical well being, not shying away from brutal scenes that find the bed-ridden critic subjected to painful insertions of suctions. At what point did you decide that you needed those scenes in the film?

I knew from the last meeting with Roger and Chaz right before we began production, during which he needed to be suctioned and I'd never seen that before and didn't know that it was something he dealt with. Chaz asked the production team to leave the room while that was happening, but Roger threw his hand up in a gesture of, ‘why?' It became clear to me then that this was a multiple-times-daily reality to his life and that we needed to show it. On the day we filmed the most graphic version of that, Chaz was not there. And she has said since that she would not have allowed us to film it. But Roger wanted it filmed and he knew that I wanted to film it. I knew it would be difficult for people to watch because it was difficult for me as I was shooting it. But it was so clear to him and me that the daily reality of his life was important to capture. This was a level of candour that was beyond what the public had seen of him despite how candid he had been. It's unusual for a subject to feel that way so completely and it's especially rare, if not unprecedented in my personal experience, for someone of his stature and notoriety to feel that way. I think that's part of what made it all the more important, because it was something that he wasn't going to shy away from. When he decided he was going to do this, he realized that he had to be all in – that he wouldn't want to see a film about him that would be any different from the kind of film he'd want to see if it was about someone else.

Having spent a great deal of time exploring the life and legacy of Ebert, have you come away with any insights about what makes a great film critic?

Just like there are many different ways someone could be a great filmmaker, I think the same is true of film criticism. For instance, I love to read Anthony Lane in The New Yorker. He is a very different critic from Roger Ebert. He has a much more erudite style, Lane's sense of humour is very different from Roger's. Both are eloquent writers, but very different kind of writers. I really like reading A. O. Scott – I feel like over the last 10 years, his writing has really blossomed as a film critic. I think what Roger's special gift was that he had an ability to write from a place of feeling about movies, and he was very clear that's what he wanted to do. You always felt that when Roger was watching a movie, he went into it wanting to love the movie. He may not, and if he didn't, too bad if you were the filmmaker, because he could be ruthlessly funny in putting it down. But you never felt that he came at movies with anything less than a real respect for how hard they are to make, and a desire to love that movie. He had a way of talking about them that was spare with the adjectives and clear – you never felt talked down to as a reader, and that's a very Midwestern sensibility. He embodied that. And there was also the political consciousness we talked about earlier, that he didn't try to hide, even though he never used movies as a soapbox for his politics. It informed his views. I think the collection of these qualities together made him a unique critical voice.

What would be your all-time favourite Ebert film review? One that has had a lasting impact on you, perhaps?

I think his reviews in general of Terrence Malick's work are really strong. I didn't see Terrence's last movie, To The Wonder, which was one of the very last reviews he wrote, but I enjoyed his review of it! (laughs) I just think he really got Malick, what makes him distinctive as a filmmaker. In particular that applies to The Tree of Life, which is why I included it as a late example of really fine criticism, but also Days of Heaven and Badlands are also really strong ones. His review of Bonnie and Clyde, which I include in the movie, is phenomenal. I just use one little piece of it, but the review as a whole is pretty amazing. As is his review of Nashville – a movie that was popular at the time, but a very different kind of film for American film. And Roger so completely got that movie.

Life Itself

Now playing exclusively at Cinéma du Parc