‘Bombay Beach’ is a Lynchian documentary gem about a community of American Dream misfits

Auteur: Michael-Oliver Harding

Bombay Beach, once a swanky vacation hot-spot in post-WWII America, located on the shores of the once-thriving Salton Sea, is now a forgotten, landlocked dump. It’s the kind of post-apocalyptic wasteland full of abject poverty, decrepit trailer homes and broken dreams one might forget still exists just a short hop from Los Angeles.

Israeli-born filmmaker Alma Har’el, an award-winning music video director who’s signed off on some of Jack Peñate, Beirut and Shearwater’s finest clips, was completely taken aback by the arresting otherworldliness and sheer mystery of Bombay Beach while location scouting for a Beirut music video. So she returned with a camera and an open mind, and spent months getting up close and personal with its cross-generational crop of male marginals.

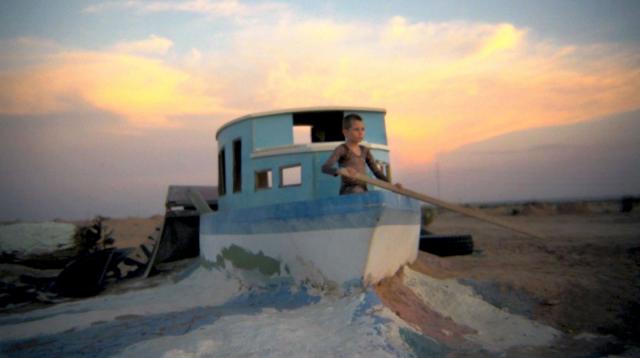

Benny in Bombay Beach

The result, Har’el’s Bombay Beach, is an impressionistic hybrid of cinema verite and experimental film. It’s a heartrending portrait of a devastated American town that never exploits nor glorifies its most unself-conscious subjects. There’s Benny, a young boy on a crippling diet of behavioural meds, whose boundless imagination allows him to look beyond his bomb-building parents and their criminal woes. There’s Red, an octogenarian hillbilly who reminisces about his John Wayne paradigm of a life – whiskey, cigarettes, and the open road. And there’s CeeJay, an aspiring football star who flees L.A. to avoid suffering the same fate as his cousin, killed in a spate of gang violence.

Bombay Beach is perhaps not for everyone: it’s assuredly quirky and embraces a trippy alternate reality, and yet it’s also a stark, moving drama. Har’el’s storytelling is fragmented in the most fascinating, surreal of ways: she stages choreographed dances with her subjects to music by Beirut and Bob Dylan, and her gorgeous, meandering cinematography celebrates the mysteries to this dying breed of American outlaws. When I reach Har’el on the line to talk about her film, which kicks off the RIDM's new monthly Docville series tonight, the contemplative filmmaker immediately finds common ground in our mutual admiration for Zach Condon’s rich tapestry of sounds. “Beirut fans united!” she says with a giggle.

Benny in Bombay Beach

Music plays a key role in your film; Beirut and Bob Dylan supply the perfect meditative score for such a singular setting. How did you come to select those artists?

When I moved to the U.S. from Israel about 4-5 years ago, Beirut was the first thing that really made me feel at home. He [frontman Zach Condon] made me feel like I had a partner in crime; and then Bob Dylan is just somebody that I always listened to in my car while I was there in the desert. It was the soundtrack of my life while I was making this film. At first I thought I’d include more artists, more music; but it never felt as right and authentic as when we just included those two.

In many ways, Bombay Beach completely flips the established script on the American Dream; you’re looking at a destitute, man-made sea shore playing host to a poverty-stricken community of misfits. Was this notion of American Dream on your mind as you were shooting?

I think it definitely was, but I don’t know that I was aware of it though. All the post-post consequences of culturally digesting American pop culture are there. What astounded me when I first went to that place was realizing that the American Dream is not one dream; it’s so easy to just say the American Dream is having your car, and a house and tons of money. I don’t think that’s here anymore, really. I mean, it is, because it’s still how a lot of people live, but I think it’s morphing and changing all the time.

The trifecta of male characters you focus on speaks volumes about a kind of masculinity at a crossroads. Each guy reveals so much about how the American Dream has changed; how it’s not what you think it is.

Absolutely, I completely agree. Red is a Wild West, Depression-era man. His dream is to have some sort of freedom. To him, freedom is being able to get by on very little. He very much sees his strength as being able to get on with very little, and not have much. To be a bum, but to enjoy it. He grew up in such a time in America when if you didn’t know how to survive on a potato, it was impossible.

Then you have someone like CeeJay, who’s a very real representation of the American Dream, because here you have someone leaving Los Angeles – which is where people from around the world come to “make it” – and he goes to the biggest ghost town in America to make it. And he does, by working hard. And then there’s Benny, who comes from a family that grew up with no education, no opportunity, who just really grew up in the desert, in the most obscure area of California.

I read about how you spent some time living in the Israeli desert, in a village that reminded you of Bombay Beach in more ways than one. Did you encounter a similar range of off-the-grid characters?

Definitely. I was renting a house in the middle of the desert on the edge of a crater. That place attracts a lot of different people who go there for different reasons: some are stuck there, were born there and can’t get out. Some have never even been to Tel Aviv although it’s a three-hour bus ride away, and some people move there to get away from the city, to get a break from a lot of things. And then you have a lot of people there who are very religious, so it was a very mixed population. It was a really strange place, it had that post-apocalyptic vibe of maybe the last place on earth, or a society trying to start over again. My imagination was running wild the entire time I lived there.

I find there’s so much criticism of the U.S. all around the world, but in a way the only things that are exported out of the country are the Hollywood versions of it. What I saw in Bombay Beach were real people, who I didn’t get to see anywhere else, living in Israel. I was moved by them, and it reminded me of Israel, because I feel like my country is also not represented for what it truly is in the media. People that I care about in Israel don’t have a voice; I think that my country fell into a lot of bad politics and violence and all these things. In a way, its image and what it has become are not the promise of what it was; the people who still live there want peace, love, and relationships of intimacy.

Your film reminds me of the work of Harmony Korine in its portrayal of unusual characters living on the fringes, and David Lynch for its surreal, otherworldly storytelling. Did you consciously set out to make a certain type of film?

Seeing [Harmony Korine’s] Gummo 12 years ago, it definitely left a very strong impression on me. And I saw a film at a much younger age, [Martin Bell’s 1984 documentary] Streetwise, about homeless children in Seattle and a whole soundtrack by Tom Waits. I saw it as a kid in Israel, and it really stuck with me. But I had no plan when I arrived in Bombay Beach. I just moved there and I started shooting. I didn’t even know what sort of people were going to be in it when I moved there. So it was just very freeing, and I shot a few things there that I loved.

I hope that I never really need to know something before I do it, because I think that such a big part of what makes something special is that you don’t know. You can allow yourself to not know, to discover things.

Bombay Beach

Plays January 26 at 7 p.m., as part of the RIDM’s new monthly Docville series

Excentris Cinema | 3536 St-Laurent Blvd.

ridm.qc.ca | bombaybeachfilm.com